For the Vidovdan Feast, we bring you the Rev. Vladyka Atanasije’s treatise on Heavenly Kingdom as Serbian spiritual base. We hope you enjoy it.

The Serbian people began to formulate their spiritual identity during the era of the Holy Brothers Cyril and Methodius (9th century), and their 5 disciples who followed (10th century). They are considered the first baptizers and enlighteners of the Serbs, as well as the other Slavs. The fruit of their work, harvested for some 2 centuries from Byzantium/Bulgaria to the Adriatic, included the gradual Christianization of the Serbs both nationally and individually, the appearance of the first ascetics and saints among the Serbs, and the first monuments of Serbia’s spiritual and secular cultures.

Starting with the time they accepted Orthodoxy and considering the subsequent history and behavior of the Serbs, it is easy to discern the basic nature of their spiritual identity. This fundamental ethos especially manifested itself from the time of Saint Sava (12th-13th centuries) and was revealed in its fullness at the Battle of Kosovo in the Serbian spiritual and historic decision to choose the Kingdom of Heaven. Mention here is made not only of the complete inner and intangible acceptance, but also of the historically tangible and concrete obedience to Christ’s Gospel words:

“See ye first the kingdom of Heaven and His righteousness, and all these things shall be yours as well.” (Mt. 6:33).

This preference for spiritual values became an inseparable part of the Serbian national soul, as well as its lifeblood in the early stages of its history. The first evidence of this appeared among the Serbian saints, who through their ascetism, virtues, and suffering were constructing a spiritual ladder to the Kingdom of Heaven for their people and who exemplified through their lives the manner in which the world, the path of history, and man’s deeds within it should be evaluated.

Thanks to the extraordinary personhood of Saint Sava (1175-1235) and his labor among the Serbs, this Orthodox Christian choice became the inherent self-identity of the Serbian people. Saint Sava has been rightfully called the all-Serbian “enlightener, the first enthroned, the Teacher of the Way which leads into the Life” - into the true, spiritual, and eternal life - as expressed by Hilandar’s poet/biographer Teodosije in the Troparion to Saint Sava. In addition to the opulent spiritual, cultural, and linguistic treasure which he left behind, Saint Sava initiated the organization of the autocephalous Serbian Orthodox Church, which contributed in an essential way to the guardianship of Serbia’s national independence. In this way the Christian faith and Church united themselves with the people, and the truths of the Gospel became the ethics of the nation as a whole. This development fatefully marked the course of the nation’s history for centuries to come.

In the history of the Serbs religious and national tolerance, as well as broad-mindedness, was well-known and attested to even before Saint Sava during that time in which the Christian Church of East and West was for the most part one. This was especially so in Duklja and the sea coast. The religious tolerance of the Serbian rulers was verified by the interesting fact that their wives and mothers came from the dynasties of other confessions. The Nemanjici were builders and benefactors of churches and monasteries belonging to other Christian confessions, but they always remained frim in the faith of Eastern Orthodox Christianity.

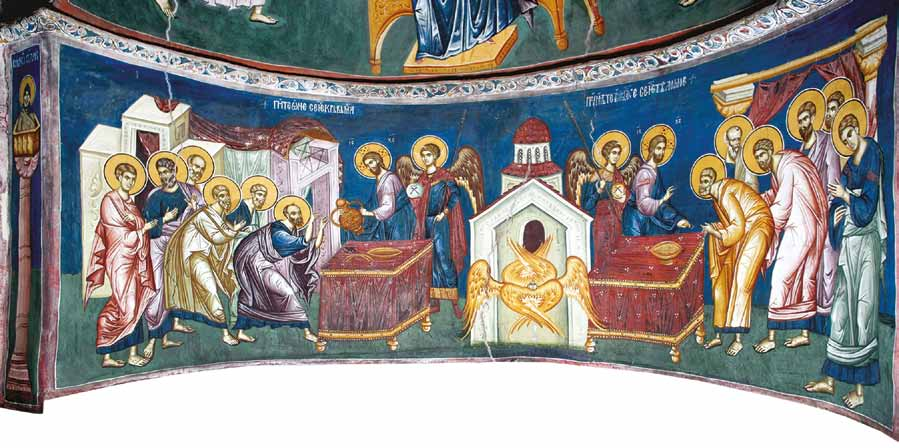

The spiritual transfiguration of Serbia in the era of Saint Sava and the other members of the Nemanjic dynasty was multifaceted. Because of the creative genius of the Church and state, it was enriched by the inclusion of folk culture (the patron saint’s day celebration, Christmas customs, the cult of ancestors, etc. …), as well as the organizational culture and art of society at large (communes, Church-people assemblies, communities, etc. …). The highest architectural and artistic accomplishments in hundreds of Serbian churches and monasteries, the biographical literature, the liturgic-monastic literature, and the state constitutional literature have made and are making “Svetosavlje” to be understood as the authentic Christian experience of the Serbian nation, or, put another way, as Orthodoxy realized in the historic experience, one nation as a whole.

Among the many forces which contributed to the making of the nation’s spiritual life were the Serbian hagiographies (the “Lives of Saints”) of the Middle Ages. The first to pen one of the biographies was Saint Sava, who wrote a life of his father, Stefan Nemanja - Saint Simeon the myrrh-flower. At the same time his brother, Stefan “the First Crowned,” also wrote about the life of their father Nemanja. Other written works followed. They include the life of Saint Sava by his disciples Domentijan and Teodosije, several biographies of Serbian archbishops and kings, life stories about holy women (St. Anastasia, St. Helen of Anjou, St. Petka, St. Euphemia), the lives of Serbian hermits (St. Procor, St. Peter Koriski, Isaia of Hilandar), as well as the lives of Serbian martyrs (St. John Vladimir - as early as the 11th Century, St. Lazar of Kosovo, the New Martyrs for Christ, etc.)

In all of these hagiographical texts, which are concurrently historical, one finds the common theme of the opting for spiritual freedom and ethical values which transcend the bare historic level of this world and life in it to penetrate metahistory and eschatology. The historic notables are portrayed in a drama with a distinct purpose, the resolution of which is found in the freedom to choose in self-determination. The only true choice is one which, through personal self-denial and sacrifice, aspires to higher, everlasting aims - a choice which aspires to the Kingdom of Heaven. It is in this spirit that Saint Sava was biographically praised foremost for his personal acceptance of spiritual values and for his selfless service to God, neighbor, and nation.

The same is true of the Serbian kings and rulers, none of whom were praised in their biographies for warfare and conquest, but primarily for their piety, beneficial endowments, and especially for their zaduzbinarstvo. Zaduzbinarstvo - i.e., the building of churches, monasteries and humanitarian institutions with the intent to achieve personal salvation and benefit their people in a lasting way. It is important to point out that a significant characteristic of Serbian hagiographical literature is that “service to the people of one’s homeland” is always understood to equal service to “God’s people,” a phrase which is not defined by nationality but rather by eschatology and the Bible - i.e. a phrase which focuses on the elevation of a people into a “covenantal” unit which does not strive for conquest and domination in the world, but rather strives for self-denial and lasting spiritual values. This rendered understandable the fact that in the conscience and living tradition of the Serbian people the ideal heroes were holy men, emulated by the rulers themselves.

In this spirit Stefan Nemanja followed his son Saint Sava in forsaking the throne to enter a monastery. They were followed by the entire “Holy Dynasty” of Serbian rulers from the Houses of Nemanjic, Lazarevic, and Brankovic, as well as a multitude of Church leaders - archbishops and patriarchs, many of whom are venerated as saints and some of whom died as martyrs. These holy persons left the Serbs the legacy and historic identity of enduring allegiance to Svetosavlje - the already accepted Gospel ethic of justice and Christian character, and the ideals of liberty and love.

All of this is corroborated by the entire Serbian folk tradition - both written and oral - folk poetry and stories, proverbs and sayings, customs and heroic deeds, and typically selfless decisions made by individuals and their greater communities, the whole nation, in certain critical moments of their history.

These are the distinctive Christian and humane qualities of our people’s soul - readiness for self-denial, sacrifice, suffering, endurance, forgiveness, and imprisonment for the sake of justice and freedom.

Another component of the Serbian spiritual identity is zaduzbinarstvo (the erection of churches and monasteries for the sake of one’s own salvation, as well as for the lasting benefit of one’s people), which is a further indication of both the direction and the degree of the people’s spiritual growth. The origins of zaduzbinarstvo can be traced to the Serbs even before Saint Sava (the church in Ston, built by Mihailo, king of Zeta, in the 11th century, or the cave-churches of the first Serbian hermits), but it especially developed since the time of Stefan Nemanja, Saint Sava, the other Nemanjici, and their heirs both within the Church and in the state. The zaduzbine were not only built by the Serbian rulers and archbishops, but also by dukes, priests, monks, and the common people. All of them built churches, monasteries, and other charitable institutions as their own, as well as for the nation - they were works done for both the glory of God and for the cultural benefit of the world.

Nonetheless, these works and the intent behind them outgrew history to meaningfully point to the Heavenly Kingdom’s enduring spiritual values. The Serbian people’s spirit of endowment (the spirit of zaduzbinarstvo) is well-attested to by the great wealth of churches and monasteries preserved throughout the Serbian lands. This holds true for the zaduzbine from the era of the Nemanjic family and even for those constructed in the later Lazarevic and Brankovic time period (14th -15th centuries), as well as those erected even during the centuries of slavery to the Turks and later. An entire cluster of churches and monasteries preserved to the present day in the relatively small area of Serbia - the surviving remnants of a glorious past and historic greatness - vividly evidences that the building of churches and monasteries was understood to be the “only needful thing” (Lk. 10:42), to which the Serbs were primarily dedicated.

It was well put by the woman writer Isidora Seklic that we Serbs: “have no castles from our past, but churches and monasteries have been sown all over; The churches and monasteries were like personal homes to everyone - rulers and shepherds, literates and illiterates, heroes and commoners.”

The Orthodox spirit of zaduzbinarstvo explains a recognized characteristic of the Serbian identity: throughout all the centuries of the past, and up until today, the spiritual and historic life of the Serbians has centered around and taken place at and within the churches and monasteries. They were and have remained the centers for national assemblies and gatherings, for self-examinations and validations, and the fundamental epicenters of faith in this great nation’s destiny. Without these holy places, the Serbian people would not be what they are - not only within Orthodoxy, but within Christendom overall. The Serbian people’s spiritual choice of Heaven over earth was manifested most fully and evidently in the fateful oral choice made in the historic battle of 1389, at which the Serbs faced the Turks on the Field of Kosovo. This choice was made by the soldiers and martyrs, who were led and given an example by the holy Prince Lazar, who himself died a martyr’s death. This exalted Christian tragedy was soon written and sung about in the Serbian Church and by folk poets. From it originated the concept of the Kosovo choice. Observes George Trifunovic, a renowned student of and an authority on the Kosovo tradition among the Serbs:

“Christ’s words about the road of suffering which leads to the Kingdom of Heaven reach through the spiritual self-denials of the first Serbian saints and through the descriptions of the poets; their culmination in the act of the martyr-death of Knez Lazar at Kosovo.”

The Serbs did not surrender to the Turks in 1389, nor did they accept the status of vassals. They instead chose to fight, since they, as a people, had well-developed spiritual values in all spheres of life - Church, state, culture, and art. Aware of the fact that a man who possesses spiritual values cannot be a slave, they chose to accept self-sacrifice and death, which is not considered a defeat, but the emergence of spiritual idealism - a source of new life and never-broken hope in the final triumph of justice and truth, of those values which belong to the Kingdom of Heavan. The Serbs, obviously aware of their statistical dis-advantage, made the decision to fight. The principle element of this acceptance of an uneven fight is the choice, a free albeit fateful decision to fight rather than surrender.

“Kosovo, 1389, was a definite affirmation of the Christian identity of the Serbian people; it was experienced as the triumph of martyrdom and in no way as a defeat. It has been lyricized in the hymns of victory with radiance and joy that the God-blessed Serbian nation was crowned with a martyr’s wreath which, from that point on, became its true and indestructible zenith. It signifies the triumph of spirit over body, eternal life over death, justice over injustice, truth over deceit, sacrifice over avarice, love over hate and force. This is what Serbian Kosovo signifies as sung about in the epic folk poetry which was inspired by this monumental, historic event.” (Dimitrije Bogdanovic). “The Kosovo choice was undoubtedly the selection of freedom in a most difficult and destructive way, but the only sure way."(Zoran Misic).

The ethic of Kosovo as the national covenant of Serbian history was even expressed by a contemporary of these events, the Serbian Patriarch Danilo III, when he lauded Knez Lazar and the Kosovo martyrs with these words in 1393: It is better to choose “death with honor and sacrifice, than life in shame,” and “let us die that we may live forever.” This and other similar liturgical and cult writings about Knez Lazar as a martyr and saint, in which his martyrdom was exalted to both a historic and a metahistoric ideal, soon became the source and inspiration of the well-known Kosovo cycle of epic poetry. This is especially evident in the poem “The Fall of the Serbian Kingdom,” in which Kosovo’s physical defeat was transformed into a spiritual victory, a Christian philosophy of tragic sacrifice converted into the moral base of the people’s mentality.

This is what made Kosovo to become and remain, in the minds of the Serbs, the place at which their historic destiny was “determined,” that is to say where they were spiritually oriented in the conviction that the resurrection of freedom and a new life can only be achieved through suffering and sacrifice. Kosovo was experienced and again many times reexperienced as our Golgotha, but also as the most certain way to the Resurrection. What enabled the Serbs to express their spiritual choice and to manifest the high ethic of Kosovo was their being rooted in the animated tradition and the creative presence of hesychasm, which in truth is the soul of Lazar’s Serbia. The Serbian churches and monasteries were the work centers of hesychasm. With this in mind, it can be concluded that the Serbia of the Lazarevic was as zaduzbinarska in spirit as the Serbia of the Nemanjici. In the zaduzbine (the monasteries) lived those who aspired to hesychasm and their many disciples. They were influential not only with the people, but also at the courts of Serbian noblemen, and especially at the court of Knez Lazar and his heirs, the Serbian despots. In spite of the gradual weakening and political disintegration of the state, hesychasm produced a true spiritual renaissance in culture, art, and religious life.

Hesychasts carried the flag of resistance to adversaries and not passive surrender. This resistance was first in strength of spirit, in the Christian philosophy of life, and in universal spirituality, all of which extraordinarily fortified the Orthodox self-consciousness of the Serbian people, whose values outlast all of the temptations of time. Hesychasm was understanding the world and man’s life in it in a way that bridged the transcendental gap between this world and the next; this rendered the hesychast’s experience of man’s destiny optimistic. It does not overlook the drama of historical living, but it transfigures life by tying it to lasting values, by emphasizing the triumph of a martyr’s death for the Kingdom of Heaven. Thus, hesychasm found itself performing the functions of Church and national defense, which was very important for the spiritual endurance of the Serbian people.

It was, thanks to this choice, that the Serbian people in the time of Turkish enslavement following Kosovo repeatedly relived their fateful Kosovo, the sacrificial choice of embracing the more difficult lot, the dramatic carrying of their cross. Even during those times when historic success could not be envisioned, the Serbs remained faithful to their “destiny,” to the Kosovo covenant.

In spite of their having lost the battle to the Turks at the Field of Kosovo, the Serbs resisted their conqueror for another half a century and for a brief period they achieved their independence. During the rule of Despot Stefan Lazarevic and during the era of the Brankovici (15th century), the Serbian people built several outstanding zaduzbine: churches and monasteries, showing once again that the erection of these edifices was considered to be their first and most important work. These zaduzbine cross the Sava and Danube Rivers, where the Serbs gradually migrated and where they brought and perpetuated their culture and the cult of venerating their saints, among which were the martyrs of Kosovo. Following their final fall to the Turks (15th century), the Serbian people did not abandon their historic memory and did not lose their spiritual identity, but they resisted mightily Islamization and they, with the faith and hope of martyrs, endured persecution, loss of property, the profaning of their sacred places, and the martyrdom of their patriarchs, priests, monks, and other leaders.

What safeguarded the integrity of the Serbian spiritual being during the centuries of slavery were Orthodoxy and the Serbian historic tradition, both of which were concentrated in the Serbian Patriarchate and in Serbian churches and monasteries - the zaduzbine. The first resurgence of the Serbs came with the renewal of the Patriarchate of Pec in 1557, under Patriarch Makarije Sokolovic, a former monk from Milesevo Monastery, the resting place of Saint Sava’s bodily remains for 3 centuries by that time, a place of common pilgrimage and a source of both spiritual and national inspiration for Serbs from all over in this time of slavery. The cult of St. Sava, with his incorruptible body lying in Milesevo Monastery, and the cult of St. Lazar of Kosovo, with his incorruptible body in Ravanica Monastery, were the two never-dying sources of both religious and national inspiration - one and the same - throughout the era of enslavement.

The importance of the renovation of the Patriarchate of Pec and the concurrent revival of religious and historic tradition manifested itself in the Serbian uprisings at the end of the 16th century. After the mighty, westward expansion of the Turkish Empire (under Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520-66) - as soon as the Turkish Empire began to weaken (especially after its defeat at the Battle of Lepanto, 1571) - the Serbs began to rise up and join the nations of Western Christendom in the war of the cross against the crescent. During the Austro-Turkish war (1593-1606), the Serbs simultaneously rose up in two places: first in Banat (1594) under the leadership of Theodore, Bishop of Vrsac, where the Serbs adorned their flags with Saint Sava’s icon, and then in Herzegovina under Metropolitan Visarion. Both of these uprisings were quickly and bloodily suppressed. The Turkish reprisals which followed were especially directed against the Serbian zaduzbine - the monasteries and churches, of which the first was the Milesevo Monastery, which was pillaged on Good Friday, 1594. Here, from the Monastery of Milesevo, by the order of the sultan, carried out by the Grand Vezier Sinan Pasha (an Islamized Albanian), the body of Saint Sava was taken, and, after having been carried throughout Serbia, was burned in Vracar in Belgrade on April 27 (May 10), 1594. But this barbarian act of malevolence - instead of intimidating the enslaved, but unconquered, people - inflamed them with the spirit of Saint Sava and the ethos of Kosovo.

Of the 3 Serbian patriarchs who ruled the Serbian people and Church in the era of the Vracar pyre, 2 out of 3 died martyrs’ deaths under the hands of the Turks: Patriarch Jovan Kantul (1614) and Patriarch Gavrilo Rajic (1659). The next great patriarch was Arsenije III Carnojevic (1674-1706), who, after the Turkish defeat outside of Vienna (1683), wholeheartedly helped the all-encompassing uprising of the people and who, with some 20,000 men, joined the Austrian army in its drive southward. With the help of these Serbian fighters, Kosovo was freed all the way to Prizren and Skoplje. But when the Austrian drive was broken at Kachanik (1690) Patriarch Arsenije was forced to move his people (some 30,000 families) north, in order to escape Turkish reprisals.

In this, “the Great Migration” (as it has been historically called), the Serbs took the body of the Holy Great-Martyr, Lazar of Kosovo, with them to their new lands (first to Sentandrey and Budim and then to the newly-built Monastery of Ravanica in Srem). Thus, the veneration of Lazar and the covenantal thought of Kosovo to liberate and reclaim the sacred places of the homeland from its foes strengthened and spread to the Serbian diaspora.

This was the time when chronicles and genealogies were recopied, the first srbljaks (service books dedicated to Serbian saints) were printed, and the time when monks and guslars (Serbian bards) traveled among the people, steered them, and kindled the memory of their past within them.

When a new Austro-Turkish war broke out soon thereafter (1718-39), the Serbs of Old Serbia and Kosovo again revolted against the Turks, this time under the leadership of Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanovic. Belgrade was liberated for a short time, and someone from among the Serbs erected a small church on Vracar in commemoration of the burning of Saint Sava’s relics there. This little church existed until 1757, when the Turks destroyed it - but that place was well-remembered and that memory was passed on from one generation to another. Soon afterward, the Patriarchate of Pec was abolished by the Turks (1766), but this again could not extinguish the spirit of the Serbian Church and the Serbian covenantal thought. Toward the end of that century, the Serbians once again rose up (Kocina Krajina) and, again, checked in blood, this uprising represented another example of self-sacrifice on the part of the Serbian nation. At the dawn of the 19th century, the Serbian Kosovo choice surfaced again, this time under the great Vozd Karadjordje Petrovic - and this time it marked the first “Resurrection of Serbia.” The Serbian insurgents were inspired by the Serbian saints and the Kosovo martyrs to fight for their freedom. The letter of the Vezier of Travnik, Mustafa Pasha, to the Turkish court testifies to this. In March of 1806 he wrote about the Serbian freedom fighters: “They sent letters to all sides . . . and as once before King Lazar came to Kosovo, they will all come to Kosovo. They constantly keep in their hands history books about the aforementioned king, and he is a great instigator of the revolts in their minds.” At this time the Serbian people in all the Serbian lands stood to fight for the liberation of Serbia and the Serbs despite the historic circumstance of its impossibility - for the Turkish Empire was still a strong European power. But the uprising in Serbia was carried on by the belief in Heaven’s justice, and in that spirit Karadjordje placed the venerable cross on his flags, under which stood hegumans, monks, priests, protopresbyters Atanasije of Bukovica and Mateja Nenadovic, the priest Luke Lazerevic, and others.

Immediately after the liberation of Serbia, which was finally completed by Milos Obrenovic and later rulers, the traditional Serbian spirit of zaduzbinarstvo was renewed, and it was then that preparations began for the erection of a memorial church in honor of Saint Sava on Vracar. On the day of the 300th anniversary of the burning of his relics a “Society for the Erection of the Church of Saint Sava on Vracar” was formed, and in only 7 days this society built the temporary, small church on Vracar, which was dedicated on April 27 (May 10), 1895. The Balkan wars of 1912 interfered and interrupted the preparations for the building of a larger church. The centuries- old Kosovo covenant and choice once again sustained the Serbs when engaged in conflict. Through their great self-sacrifice and heroism they finally succeeded in abolishing the Turkish yoke - which enslaved them for half a millennium - and in freeing the great martyred land of Kosovo.

In World War I Serbia was once again placed in a situation of complete disadvantage, but she, once again, refused to accept the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum, chose the Kingdom of Heaven, and accepted conflict with the powerful Hapsburg Empire, much like David against Goliath. After the war and the creation of Yugoslavia (1918), the initiative for the building of the Saint Sava Church on Vracar was renewed, as was the old spirit of Serbian zaduzbinarstvo. The most prominent standard-bearers of this spirit at that time were King Peter I (exemplified by his zaduzbina, the Saint George Church at Oplenac) and Patriarch Varnava Rosic.

Only 2 decades afterward came the tragic events of World War II and on the eve of their greatest martyrdom the Serbs once again revealed that the Kosovo choice of Heaven over earth was very much alive within them when they, after Yugoslavia was blackmailed into acquiescing to the Tri-Partite Pact with the Fascist Axis, spurned that Pact (March 27, 1941). Patriarch Gavrilo Dozic went on Belgrade Radio and proclaimed, in the name of the Serbian people, that: “We have once again chosen the Kingdom of Heaven, that is the Kingdom of God’s truth and justice, of the people’s unity and freedom. This is an eternal ideal, carried in the hearts of all Serbian men and women, kept aflame in the holy places of our Orthodox zaduzbine - the monasteries and churches …”

Thus, once again, deeds proved that the ideal of the Kosovo choice is ever-present in the historic destiny of the Serbian people. This time the Serbian choice of the Kingdom of Heaven was paid for by hundreds of thousands of innocent Serbian lives whose only “guilt” lay in belonging to the Serbian Orthodox people of Saint Sava.

The church that is being erected on the ashes of the burned relics of Saint Sava on Vracar (in Belgrade) is, for these reasons, at the same time a monument to the martyred people of the great Kosovo covenant.